This week, Target announced that its 2013 data breach had been resolved for $18.5 million. That breach involved access to consumer data for over 110 million Target customers. Public service accountants should take notice. Whether you work with a school district, a fire department, police department, or any other public service entity, you will access and be responsible for sensitive data. Cougar Mountain Software’s DENALI allows you to breathe easy because its accounting solution solves common public service accounting security challenges with these five enhanced security features:

This week, Target announced that its 2013 data breach had been resolved for $18.5 million. That breach involved access to consumer data for over 110 million Target customers. Public service accountants should take notice. Whether you work with a school district, a fire department, police department, or any other public service entity, you will access and be responsible for sensitive data. Cougar Mountain Software’s DENALI allows you to breathe easy because its accounting solution solves common public service accounting security challenges with these five enhanced security features:

Internal controls are the necessary rules, technology, and structure that help catch honest errors and dishonest acts. These safeguards represent a much broader financial stewardship than simple fraud prevention. When well deployed, maintained, and enforced, these controls assure an organization will achieve its mission and its goals. In this post, we’ll be exploring the third and last component of truly effective internal controls: a culture of integrity (A.K.A. the ultimate success story).

Internal controls are the necessary rules, technology, and structure that help catch honest errors and dishonest acts. These safeguards represent a much broader financial stewardship than simple fraud prevention. When well deployed, maintained, and enforced, these controls assure an organization will achieve its mission and its goals. In this post, we’ll be exploring the third and last component of truly effective internal controls: a culture of integrity (A.K.A. the ultimate success story).

If you missed the series finale on this subject you can catch up HERE, otherwise, skim the following post-op for a synopsis of the issues at play.

“How do you encourage good behavior and discourage bad behavior?” asks Denise McClure, CPA, CFE, in our 2nd webinar about fraud prevention, “By heightening the risk of consequences for that bad behavior.”

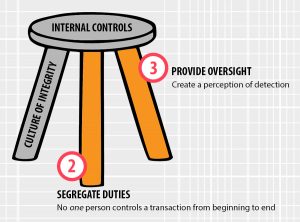

Internal controls are a three-legged stool. The first leg — a culture of integrity — is discussed in the 3rd webinar. The second leg is segregation of duties, which ensures that no one person controls a transaction from beginning to end. The third leg of the stool is the necessary provision of oversight. Easing into a disclaimer, Denise explains, “How you implement checks and balances in your organization will be different based on what kind of accounting system you have, the skills and abilities of your employees, and several other factors. There is no one, right way to do it.” It’s a classic Goldilocks scenario. Too many internal controls can lead to a paranoid work environment, inefficient processes, and ‘handcuffed’ employees who don’t have enough maneuverability or trust to do their jobs. Too few internal controls, and there is a loss of respect for the organization, lethargic job performance, and — the subject of the second webinar — a perceived opportunity to capitalize on that disorganization and dysfunction by committing a fraudulent offense with a minimal chance of being caught.

Responsibility of Board Members

Responsibility of Board Members

According to research published in the Marquette report and the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) Report to the Nations on Occupational Fraud & Abuse (2016), those who commit fraud (for the first time) are among the most trusted in their organization(s). These are competent, educated employees that have risen to a level in their careers where they have access to assets and less oversight. Exceptionally few perpetrators are below 30 years of age or above 60 years. Individuals between those two ages account for 83% of cases. While data suggests that fraud is an equal opportunity crime (both genders commit the offense in equal numbers), men steal around 25% more than their female counterparts. Another interesting factoid: the longer individuals are employed, the more they steal.

Forensic accountant and Certified Fraud Examiner, Denise McClure, explains the story behind these numbers. Seasoned employees steal more than their untried workmates because they can justify it, she says. “I should have gotten a raise years ago,” “I’m under-appreciated,” “I’m only borrowing this money,” are all common rationalizations-turned-manifestos that help first-time offenders justify their illicit behavior. In the 1940s, Donald Cressy, a criminology student at Indiana University, hypothesized that there were three conditions necessary for someone to commit fraud: 1) a non-sharable financial pressure, 2) opportunity, and 3) rationalization. Today, experts call this combination the Fraud Triangle.

Embezzlement is a Pattern of Behavior, and It Doesn’t Happen Overnight

Embezzlement is a Pattern of Behavior, and It Doesn’t Happen Overnight

If you think embezzlement is only something that happens at large corporations — where one bad egg out of hundreds of employees can escape with cash unnoticed — think again. Occupational fraud, or the misuse of an organization’s resources by someone within the organization, is a threat to companies and nonprofits both big and small.

But fraud isn’t something that happens overnight. On average, fraudsters can get away with their crimes up to 18 months before they’re detected, according to the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners’ (ACFE) 2014 fraud report. That same report showed that employees in certain positions are more likely to commit fraud than others. Executives committed fraud in 19 percent of cases studied, followed by managers (36 percent) and employees (42 percent).